FEB 15

2012

The Trouble with Pork, Part 2

Filed under: Liver Disease, Pork

from Perfect Health Diet:

http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=5624

So it looks like pork consumption is correlated with cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, and multiple sclerosis (Pork: Did Leviticus 11:7 Have It Right?, Feb 8, 2011). Why?

There are a number of potential dangers from pork, and to give each due consideration will require two posts. I’ll look at a few candidates today, and save my top candidate for Thursday.

Omega-6 Fats

Omega-6 fats are a health villain: Excess omega-6 contributes to general inflammation, fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and impaired immune function.

And pork can be a major source of omega-6 fats. Nutritiondata.com lists the omega-6 fraction of lard at 11%. But the omega-6 fraction can be highly variable, depending on the pig’s diet. Chris Masterjohn recently reported that the lard used in the “high-fat” research diet was 32% polyunsaturated, nearly all of it omega-6:

The graph shows the difference between the actual fatty acid profile as determined by direct analysis of the lard and the previously reported fatty acid profile, which had been estimated using the USDA database. We can see that the actual fatty acid profile is much higher in PUFAs, at the expense of both saturated and monounsaturated fats. In fact, the company had originally estimated the diet to provide 17 percent of its fat as PUFA, but now estimates it to provide a whopping 32 percent!

Chris further reported that feeding the pigs a pasture and acorns diet would reduce lard PUFA levels to 8.7%, and feeding them a Pacific Islander PHD-for-pigs diet of coconut, fish, and sweet potatoes would reduce lard PUFA levels to 3%.

So the omega-6 content can cover a 10-fold range, 3% to 32%, with the highest omega-6 content in corn- and wheat-fed pigs who have been caged for fattening. Corn oil and wheat germ oil are 90% PUFA, and caging prevents exercise and thus inhibits the disposal of excess PUFA. Caging is a common practice in industrial food production; here is a picture of sows in gestation crates:

And here are some Chinese pigs in shipping cages for transport to market:

The Wall Street Journal reported Monday that McDonald’s, following Chipotle, has asked its pork suppliers to stop using gestation stalls, and the largest US hog producer, Smithfield Farms, has begun a 10-year plan to move pigs from small stalls into roomier “group housing systems.” So perhaps the omega-6 content of commercial pork will come down.

How much omega-6 are people actually getting from pork? In the Bridges database, the range in pork consumption across countries was 2 to 80 kg/yr, or 5 to 200 g/day. If this is from industrially raised pigs whose fat is 30% omega-6, then this works out to 0.25% to 10% of energy as omega-6 fats from pork. In most countries, pork is either the primary source of omega-6 fats or the second source after vegetable oils.

Moral of the story: If you’re going to eat a lot of pork, there are real benefits to finding a source of naturally raised pigs fed a healthy diet.

Aside: On a similar diet, human adipose tissue develops almost identical omega-6 levels to pig lard. The Finnish Mental Hospital Study [1] [2] [3], discussed in our book on pages 63-65, showed that on a normal dairy-rich hospital diet human adipose tissue is less than 10% omega-6, but on a soybean oil rich diet adipose tissue becomes 32% omega-6.

American diets have traversed this range in recent decades. Here is a plot of subcutaneous fat omega-6 levels from Stephan Guyenet:

But can omega-6 fats explain the remarkable correlation between pork consumption and liver cirrhosis mortality, hepatocellular carcinoma, and multiple sclerosis?

Polyunsaturated fats are usually a factor in liver diseases. As we discuss in the book (pp 57-58), polyunsaturated fats – either omega-6 or omega-3 – combined with alcohol or fructose are a recipe for fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome, especially if micronutrient deficiencies figure in the mix. Two of the studies cited in the book:

- Mice fed 27.5% of calories as alcohol developed severe liver disease and metabolic syndrome when given a corn oil diet (rich in omega-6), but no disease at all when given a cocoa butter diet (low in omega-6). (The first line of this paper reads, “The protective effect of dietary saturated fatty acids against the development of alcoholic liver disease has long been known”.) [4]

- Scientists induced liver disease in mice by feeding alcohol plus corn oil. They then substituted a saturated-fat rich mix based on beef tallow and coconut oil for 20%, 45%, and 67% of the corn oil. The more saturated fat, the healthier the liver. [5]

George Henderson, who got us started on this series, links to more papers connecting omega-6 fats to liver cirrhosis.

So: Pork can be a major source of omega-6 fats; and omega-6 fats are a cause of liver cirrhosis.

However, there are several reasons for thinking that omega-6 fats cannot be the primary reason pork raises mortality from our three diseases.

First, vegetable oil consumption seems to be largely uncorrelated with the pork-associated diseases. If omega-6 fats were the primary cause then vegetable oils should have been as strongly correlated as pork. Yet there are plenty of cases of high vegetable oil and low pork consumption (eg Israel), or low vegetable oil and high pork consumption. Disease rates track pork consumption only.

Second, high intake of omega-6 fats causes a mild elevation of risk for a wide range of diseases, much like obesity (which high omega-6 intake causes). Yet pork is associated with extreme elevation of three diseases, and little association with other diseases – not at all the pattern we would expect for omega-6 fats.

Overall, I think we can say that omega-6 fats are probably a contributing factor in liver disease and liver cancer, possibly in multiple sclerosis, but they are unlikely to be the primary factor in the high correlation between pork consumption and liver cirrhosis mortality, liver cancer mortality, and multiple sclerosis.

Processed Meat Toxins

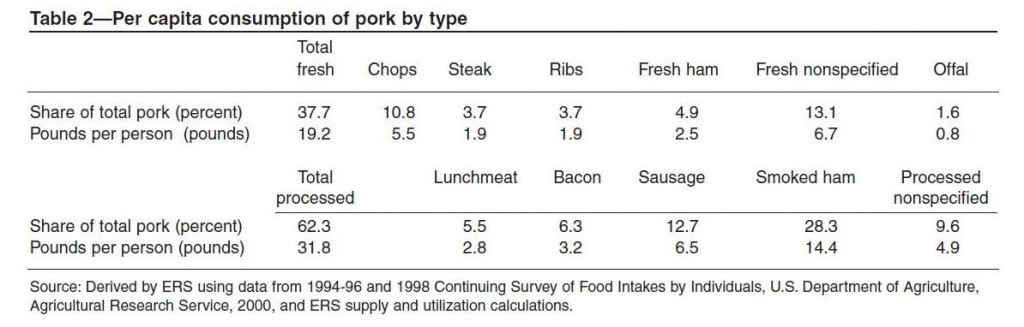

In many countries, most pork consumption is in the form of processed meats. In the United States, about two-thirds of pork is processed. Here is a table (hat tip: Mary Lewis):

Smoked ham is 28% of US pork consumption, sausage is 13%, bacon 6%, processed lunchmeat 6%, and other forms of processed pork another 10%. Among fresh pork cuts, pork chops lead with 11% of US consumption.

In epidemiological studies, processed meat consumption is often associated with poor health. The strongest association is for colorectal cancer [6] and other cancers of the digestive tract, liver, and prostate.

The main types of processing are curing and smoking. Smoking introduces to the meat smoke toxins such as phenols, aldehydes, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Curing uses salt, sugar, and nitrite, and while these are fairly benign on their own, various toxins can be formed from them, notably glycation products from the sugar and “N-nitroso compounds” such as nitrosamines from the nitrite.

Some people have concerns about the salt in processed pork. MScott provided evidence that the salt could promote peroxidation of omega-6 fats. Vladimir Heiskanen sent me a link to a blog post arguing that upsetting the sodium-potassium balance could be important:

Dr. Kublina also stressed that people must understand the massive impact that processing has on foods. She cites, for example, that 100 g of unprocessed pork contains 61 mg of sodium and 340 mg of potassium, but turning this into ham alters that ratio significantly, to yield a whopping 921 mg of sodium and, to boot, reduces the potassium content to 240 mg.

On the other hand, john linked to a paper showing that bacon protected against colon cancer,probably due to its salt content. Personally, I think salt is quite healthy, even at the levels contained in bacon, as long as one drinks water and eats vegetables for potassium.

Of all the toxins in processed pork, the most plausible causal agent for our three diseases are the N-nitroso compounds. These compounds are highly abundant in processed pork:

N-nitroso content of food items ranged from <0.01?g/100 g. to 142 ?g/100 g and the richest sources were sausage, smoked meats, bacon, and luncheon meats. [7]

The most common N-nitroso compound in pork products is N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), followed by N-nitrosopiperidine (NPIP), N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), N-nitrosopyrrolidine (NPYR), N-nitrosomorpholine, and N-nitrosothiazolidine (NTHZ).

Nitrosamine levels are increased by high-temperature cooking: “Frying of bacon and cured, smoked pork bellies led to substantially increased levels of NPYR.” [8] In general, high-temperature cooking of meats is a bad idea, as it can generate mutagenic and carcinogenic compounds even in fresh meat. [9]

N-nitroso compounds are known causal agents for liver cancer. Scientists commonly use N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA) to induce hepatocellular carcinoma in rats (669 citations, eg [10]). In primates, N-nitroso compounds specifically cause cancers of the liver:

Conversely, all except two of the N-nitroso compounds were carcinogenic. Diethylnitrosamine (DENA) was the most potent and predictable hepatocarcinogen in cynomolgus, rhesus, and African green monkeys. [11]

A Finnish study found an increased risk of colorectal cancer with exposure to N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) from smoked and salted meats, mainly fish and pork [12]. In China, intake of N-nitroso compounds correlates with the incidence of esophageal cancer. [13]

So it seems like we have a likely causal agent here linking pork to liver cancer.

But not so fast!

Although N-nitroso compounds undoubtedly can cause liver cancer, there is a big obstacle to attributing the correlation of human liver cancer with pork consumption to the N-nitroso compounds in processed pork. This is that human liver cancer rates seem to be more strongly related to consumption of fresh pork than processed pork.

I’ve seen several studies showing this, and none showing the reverse. Here’s an example: “A prospective study of red and processed meat intake in relation to cancer risk” [14]. Remember, red meat includes pork, and pork is the most dangerous red meat; processed meat is mainly processed pork.

Here is the hazard ratio of various cancers for the top quintile versus bottom quintile of red meat intake:

Liver cancer has the highest hazard ratio, 1.61.

Here are the hazard ratios for processed meat:

Liver cancer is eleventh most likely among the cancers, and the hazard is insignificant.

Here’s another study, an analysis of colorectal cancer rates in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC), which also supports the idea that (a) pork is worse than beef and (b) fresh pork is worse than processed pork:

In analyses of subgroups of red meats, colorectal cancer risk was statistically significantly associated with intake of pork (for highest versus lowest intake, HR = 1.18, 95% CI = 0.95 to 1.48, Ptrend = .02) and lamb (HR = 1.22, 95% CI = 0.96 to 1.55, Ptrend = .03) but not with beef/veal (HR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.86 to 1.24, Ptrend = .76). In analyses in which intake of each meat was mutually adjusted for intake of the other meats, only the trend for increased colorectal cancer risk with increased pork intake remained statistically significant (Ptrend = .03). Intakes of ham (for highest versus lowest intake, HR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.90 to 1.37, Ptrend = .44), of bacon (HR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.79 to 1.17,Ptrend = .34), and of other processed meats (mainly sausages) (HR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.84 to 1.32, Ptrend =.22) were not independently related to colorectal cancer risk. [15]

Beef is harmless, lamb is not statistically significant after adjustment for pork intake, but pork was harmful in all analyses. However, processed pork had lower hazard ratios than fresh pork, and bacon even appeared protective!

Before I conclude this post, let me present one more fact. This is that fiber consumption is protective against pork-induced cancer. Here is representative data, from [15]:

Look at panel B: With high fiber intake there is essentially no additional cancer risk; but if fiber intake is low, then pork consumption is much more effective at elevating cancer rates.

Conclusion

So let’s add up the evidence and see where it leads:

- First, the only potentially dangerous component of fresh natural pork, omega-6 fats, can’t account for the data.

- Second, processed pork, which has other dangerous compounds like N-nitroso compounds, actually appears safer than fresh pork.

- Third, fiber is protective against pork dangers.

To me these suggest that an infectious pathogen is the cause we are looking for.

Consider: Traditional methods of processing pork, such as salting, smoking, and curing, areantimicrobial. They were developed to help preserve pork from pathogens. So if processed pork is less risky than fresh pork, we should look for a pathogen that is reduced in number by processing.

If a pathogen is the cause, then it makes sense that fiber would be protective. Fiber increases gut bacterial populations. Gut bacteria get “first crack” at food and release proteases and other compounds that can kill pathogens. Also, a large gut bacterial population makes for a vigilant immune system at the gut barrier, making it more likely that pathogens will fail to enter the body. The gut flora are a valuable part of the gut’s immune defenses.

In my next post I’ll look at the pathogens that can infect both pigs and humans, and see (1) if there is a likely candidate for the association of pork consumption with liver cirrhosis, liver cancer, and multiple sclerosis, and (2) how we can best protect ourselves against this threat.

References

[1] Miettinen M et al. Effect of cholesterol-lowering diet on mortality from coronary heart-disease and other causes. A twelve-year clinical trial in men and women. Lancet. 1972 Oct 21;2(7782):835-8. http://pmid.us/4116551.

[2] Turpeinen O et al. Dietary prevention of coronary heart disease: the Finnish Mental Hospital Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1979 Jun;8(2):99-118. http://pmid.us/393644.

[3] Miettinen M et al. Dietary prevention of coronary heart disease in women: the Finnish mental hospital study. Int J Epidemiol. 1983 Mar;12(1):17-25. http://pmid.us/6840954.

[4] You M et al. Role of adiponectin in the protective action of dietary saturated fat against alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Hepatology. 2005 Sep;42(3):568-77. http://pmid.us/16108051.

[5] Ronis MJ et al. Dietary saturated fat reduces alcoholic hepatotoxicity in rats by altering fatty acid metabolism and membrane composition. J Nutr. 2004 Apr;134(4):904-12.http://pmid.us/15051845.

[6] Santarelli RL et al. Processed meat and colorectal cancer: a review of epidemiologic and experimental evidence. Nutr Cancer. 2008;60(2):131-44. http://pmid.us/18444144.

[7] Stuff JE et al. Construction of an N-nitroso database for assessing dietary intake. J Food Compost Anal. 2009 Dec 1;22(Suppl 1):S42-S47. http://pmid.us/20161416.

[8] Ellen G et al. N-nitrosamines and residual nitrite in cured meats from the Dutch market. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 1986 Jan;182(1):14-8. http://pmid.us/3953157.

[9] Sinha R. An epidemiologic approach to studying heterocyclic amines. Mutat Res. 2002 Sep 30;506-507:197-204. http://pmid.us/12351159.

[10] Peto R et al. Effects on 4080 rats of chronic ingestion of N-nitrosodiethylamine or N-nitrosodimethylamine: a detailed dose-response study. Cancer Res. 1991 Dec 1;51(23 Pt 2):6415-51. http://pmid.us/1933906.

[11] Thorgeirsson UP et al. Tumor incidence in a chemical carcinogenesis study of nonhuman primates. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1994 Apr;19(2):130-51. http://pmid.us/8041912.

[12] Knekt P et al. Risk of colorectal and other gastro-intestinal cancers after exposure to nitrate, nitrite and N-nitroso compounds: a follow-up study. Int J Cancer. 1999 Mar 15;80(6):852-6. http://pmid.us/10074917.

[13] Lin K et al. Dietary exposure and urinary excretion of total N-nitroso compounds, nitrosamino acids and volatile nitrosamine in inhabitants of high- and low-risk areas for esophageal cancer in southern China. Int J Cancer. 2002 Nov 20;102(3):207-11.http://pmid.us/12397637.

[14] Cross AJ et al. A prospective study of red and processed meat intake in relation to cancer risk. PLoS Med. 2007 Dec;4(12):e325. http://pmid.us/18076279.

[15] Norat T et al. Meat, fish, and colorectal cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into cancer and nutrition. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Jun 15;97(12):906-16.http://pmid.us/15956652.

No comments:

Post a Comment